If you or a loved one has a disability, the RDSP could be the perfect way to secure a solid financial future.

As the single mother of a disabled daughter, 52-year-old Mississauga resident Rita Kerkmann worries about what will happen after she’s gone. Her teenage daughter Jodi is developmentally delayed and has autism, and Kerkmann wants her to have the financial resources for a good quality of life. “Unfortunately, a lot of kids aren’t getting quality support these days,” she says. “A lot of them are just watching TV, and that’s not what I want for her.”

Jodi will need around-the-clock care for the rest of her life, and it won’t be cheap. “There aren’t a lot of day programs out there for the disabled. Even if you find one, you may be paying privately for it and the going rate is around $80 per day.” Kerkmann also wants to make sure Jodi can enjoy activities in the evening. “My daughter’s a big football fan. Like any other person, she enjoys live games every once in a while, which cost money. She deserves to be out in the community and enjoying activities.”

That’s why the moment Canada’s Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) became available in 2008, Kerkmann didn’t waste a minute going to her bank to set up an account. She knew the lucrative federal program would go a long way to ensuring Jodi would thrive long after she was gone. “It’s sad that more people aren’t using RDSPs,” she says.

Kerkmann is right. Despite this tool’s ability to improve the lives of people with disabilities, only 78,000 of 500,000 eligible Canadians have opened an RDSP since the program’s inception. This is a disconcerting fact given that the disabled often face difficulty seeking employment and often earn lower wages when they are working.

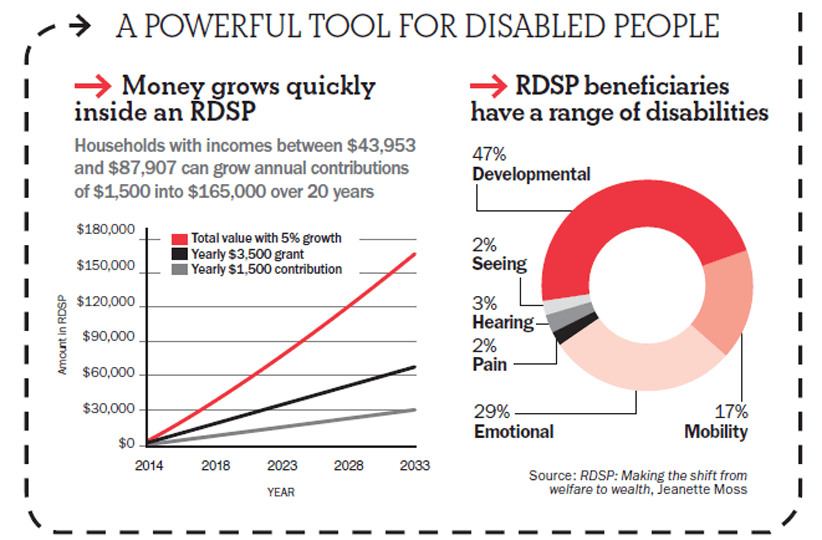

Like the Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP), money placed in an RDSP grows tax-free and also benefits from grants chipped in by the government. But whereas RESPs can provide a sizeable 20% return on contributions of up to $2,500 per year, RDSP contributions can net a staggering 300% return, depending on your income level. In some cases, the government will give you money even if you can’t afford to make any contributions.

Those already benefitting from RDSPs know the shortfalls of the current system. Chief among complaints are issues involving complicated paperwork and limited investment options and assistance from the banks who provide RDSP accounts. “I know the benefits of the program so I muddle through, but find the process significantly frustrating,” says Scott Wignall, a 41-year-old deaf disability worker in Winnipeg who manages his own RDSP. More frustrating for him is watching his fellow disabled peers not take advantage of RDSPs. The bottom line is that despite the program’s challenges, for many disabled Canadians these plans represent an incredible opportunity to secure a prosperous future.

What are the benefits?

The RDSP is a savings plan designed to help disabled adults or the parents of disabled children build up significant amounts of money for expenses later in life. “Think of it as a pension plan for those with disabilities so they’ll have money for retirement,” says Joel Crocker, director of the Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN), the Vancouver-based organization instrumental in the development of RDSPs.

A key benefit of using RDSPs is they allow money to grow tax-sheltered, meaning the individual for whom the account is set up (the beneficiary) never pays tax on earnings until funds are withdrawn. While there’s no limit to how much you can put into an RDSP each year, there is a $200,000 lifetime contribution limit. Because the plans are meant to be withdrawn after 60, no more contributions can be made at the end of the year the beneficiary turns 59.

Without question, the RDSP’s biggest advantages are the Canada Disability Savings Bonds (CDSBs) and Canada Disability Savings Grants (CDSGs). These are contributions provided by the federal government that supply up to $4,500 a year in direct assistance annually—and up to $90,000 over a beneficiary’s lifetime. But the amount of CDSG or CDSB a beneficiary can qualify for depends on family income, defined by the beneficiary’s age. “When the child reaches the age of majority, it’s the beneficiary’s own income that is applicable,” says Fred Ryall, a Toronto-based estate planner. Another factor to consider, adds Toronto fee-for-service planner Jason Heath, is that once beneficiaries turn 49, they are no longer eligible to receive the grants or bonds—“all the more reason to start an RDSP as soon as possible,” Heath says.

The CDSB is meant for disabled people with lower earnings. Those with family incomes less than $25,584 can receive $1,000 of government money annually for up to 20 years (or until 49)—regardless of contribution amounts. A pro-rated portion of the $1,000 yearly amount is also available when family income exceeds $25,584 but is under $43,953. “Being eligible for the CDSB doesn’t require anyone to put in a penny to receive government money,” says Rita Kerkmann. “I don’t understand why you wouldn’t sign up.”

Regarding the CDSG, households earning more than $87,907 receive a 100% match from Ottawa on the first $1,000 of contributions a year (until age 49). But when a family’s income is less than $87,907, the government kicks in 300% in matching grants on the first $500 contributed and 200% in grants on the next $1,000 of contributions. The maximum amount of CDSG a beneficiary can qualify for is $3,500 per year and up to $70,000 over a beneficiary’s lifetime. To receive the full amount of grant every year, you’ll need to contribute either $1,000 or $1,500 a year, depending on income level.

If you haven’t started an RDSP, CDSG and CDSB can be calculated back to the past ten years (starting in 2008) for existing accounts, or accounts opened in 2011 or later. That means you may become eligible for an annual grant as high as $10,500 and a bond of up to $11,000.

Who can set up an RDSP?

An RDSP can be opened for beneficiaries provided they are under age 60, are residents of Canada, have valid social insurance numbers and are eligible for the disability tax credit (DTC). That may sound fairly straightforward, but qualifying for the DTC can be an onerous task, says Alan Whitton, an Ottawa civil servant who authors the Canadian Personal Finance Blog (canajunfinances.com). It requires filling in the T2201 Disability Tax Credit Certificate—a long, complicated medical form Canada Revenue Agency requires as proof of disability. Whitton knows this from first-hand experience, having already gone through the process for his autistic son Rhyse, an inquisitive eight-year-old with a passion for computers and trains.

“When I first tried to apply, my family doctor didn’t know how to fill the form in,” Whitton recalls. “In Ottawa, we’re lucky enough that the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario has a specialized ward for autism service. The psychologists who filled in our form had done it several times before. But for those living in an outlying area without access to a major hospital, the process can be quite difficult and overwhelming.” To this end, Whitton’s blog provides detailed instructions about the process of applying for the DTC and fine points about how the paperwork must be filled out. Another good source of information is PLAN’s website rdsp.com, which provides tutorials on applying for the DTC (including guidance if you’re rejected).

Disabled adults without an impairment that prevents them from entering into a contract are responsible for opening their own RDSP. That’s what Scott Wignall did in 2008, when his father first told him about the program. But for disabled adults unable to enter into a contract, a qualifying family member—including a spouse, common-law partner or parent—can become the “plan holder” who is in charge of setting up and managing the RDSP. Similarly, if the RDSP beneficiary is a minor, a parent or authorized guardian can open an RDSP on his or her behalf. However, when that beneficiary reaches the age of majority he or she must take over the account unless their disability prevents them from doing so.

It’s important to note a beneficiary can only have one RDSP open at any given time (except when transferring from one RDSP to another), but an RDSP can have many different plan holders. Moreover, a plan holder acting for a beneficiary doesn’t have to be a resident of Canada. Anyone who has the written permission of the plan holder can contribute to the RDSP.

What can you invest in?

Once a disabled person has qualified for the DTC, an RDSP account can be opened up at any of Canada’s major banks. Problematically, though, investment options are limited at most of these financial institutions because RDSP plan holders can buy only the banks’ in-house GICs or mutual funds. However, TD Waterhouse’s discount brokerage service is an exception. It lets RDSP clients purchase any type of investment product—including individual stocks, ETFs, index mutual funds or low-cost actively managed mutual funds.

Until recently, Rita Kerkmann had been unaware that this type of choice was available. She currently has her disabled daughter’s RDSP set up with BMO mutual funds, but the fees attached to these products have been an ongoing concern for her. “At some point, I don’t want to be limited to paying the mutual fund fees,” she says. “Maybe I’ll transfer to TD Waterhouse or maybe I’ll wait for a little bit and hopefully BMO InvestorLine will open it up as well.”

One thing Kerkmann does enjoy about her BMO RDSP account is the option of automatic payments—something all the banks offer when you’re buying their actively-managed funds. But if you want to make lump-sum deposits it requires a phone call to their investor centre, says Scott Wignall, who also uses BMO. “My specific disability is deafness. This means I do not use the telephone.” Instead, Wignall has to make an appointment at his branch to carry out the transaction in person. “I’m confident and comfortable with lip-reading, but not every deaf person will be,” he adds.

It’s the same with TD Waterhouse’s discount brokerage, says Alan Whitton. He has to place money into his normal TD Waterhouse trading account, then call the bank and ask for the money to be transferred to his son’s self-directed RDSP account. “The whole exercise usually ends up taking up a half hour of my day, as opposed to the few minutes it would take if I had the option of transferring funds online,” says Whitton.

Advocates for the disabled like Joel Crocker are optimistic the situation will improve over time. “We’re hoping that as the banks get more pressure to accommodate people with disabilities, they will allow more flexibility with their options.”

Rollover and save

Another great way the government enables RDSPs to be built up quickly is by allowing the proceeds from certain registered savings plans to be transferred tax-free directly into an RDSP. These rollovers include RESPs (provided the plans share a common beneficiary), and RRSPs, RRIFs and certain lump-sum amounts paid from registered pension plans (provided the plan holders are the beneficiary’s deceased parents or grandparents).

To take advantage of these rollover options, the beneficiary’s RDSP must have available contribution room. None of the proceeds of these rollover plans are eligible for government grants or bonds.

How to take money out

There are two types of payments that can be paid to an RDSP beneficiary: disability assistance payments (DAPs) and lifetime disability assistance payment (LDAPs).

DAPs are one-time withdrawals that can be paid any time after the RDSP is established. But it’s important to note that any grants or bonds received within the last 10 years must be partially repaid—$3 for everyone $1 withdrawn—as the plan is intended to encourage long-term savings. This means if a beneficiary had only held funds for a few years and then tried to redeem $1,000, he or she would have to pay the government back $3,000 worth of CDSBs and CDSGs.

LDAPs are annual withdrawals that begin by the end of the year in which the beneficiary turns 60, then continue for the life of the beneficiary. There are maximum annual withdrawal limits if government contributions exceed private contributions, as well as minimum payouts based on a formula provided by the CRA.

Regarding taxation, when you make a withdrawal from an RDSP, your private contributions are not subject to tax. However, both federal contributions (CDSB and CDSG) and income and growth from the RDSP account will be taxed as income.

Does the RDSP impact government benefits?

First, the good news: “In every province and territory the RDSP is exempt as an asset,” says Joel Crocker of PLAN. This means RDSP assets won’t affect eligibility for provincial benefits such as the Ontario Disability Support Program. When money is paid out of a RDSP it won’t impact any federal benefits, such as the Canada Child Tax Benefit, the HST/GST Credit, Old Age Security or Employment Insurance.

But depending on the province or territory, income-tested benefits could be impacted. That’s because income from RDSP withdrawals may be completely or only partially exempted. For instance, in B.C. money withdrawn from an RDSP is completely exempt from being claimed as family income, but that’s not the case in New Brunswick. Check with your provincial government to determine how you might be impacted.

Over the long haul

It’s possible beneficiaries could lose their DTC status if they are no longer considered severely impaired. This is something that concerns Alan Whitton because certain types of disabilities, like his son’s autism, require DTC reapplication every 10 years. If Rhyse, who has high-functioning autism, was later denied the DTC, Whitton will have two choices. He could collapse Rhyse’s RDSP, but that would involve repaying all CDSG and CDSB amounts collected within the last 10 years. Or, he could apply for an “election” in which a medical practitioner certifies that the beneficiary’s condition will likely return within the next five years. During this dormancy period, no contributions can be made, the RDSP wouldn’t be eligible for grants or bonds, and carryforward rules wouldn’t apply in the event that the disability returned. Withdrawals, however, can be still made.

When a beneficiary dies, the RDSP must be closed, and any grants and bonds obtained within the last 10 years must be repaid. All amounts remaining in the plan must then be paid out to the beneficiary’s estate to be taxed accordingly.

The RDSP certainly has its imperfections, but overall it’s a huge step forward for disabled people and their families. Looking at Rita Kerkmann’s situation, in the six years since she started using an RDSP, she’s seen her $8,000 of contributions grow to more than $32,000. She expects the funds will keep growing quickly in the years to come. “With the return I’m getting on my money, you can’t do better,” she enthuses. “It gives me peace of mind for my daughter’s future.”