June 27, 2014

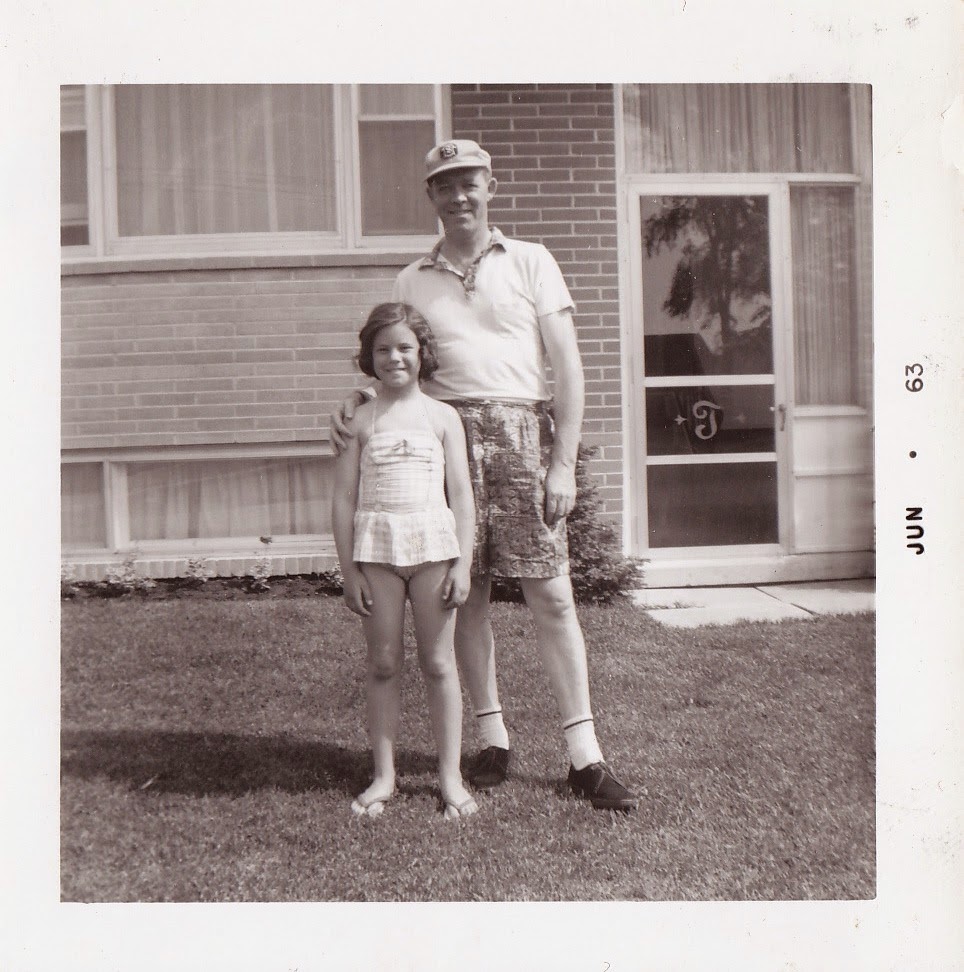

After my Dad passed away in 1975 following his third stroke, I was angry. Really, really angry. I would sit in church, look at Christ on the cross and fume, “why does everyone go on and on about YOUR suffering?! That was NOTHING compared to what my Dad endured!” All these years later, the anger has waned, but I still haven’t come to terms with what happened back then. My father was too young. He was from a generation that abhorred dependency, so he suffered great humiliation. I felt somehow abandoned by ‘the rock’ of our family, so I floundered personally. The wounds are scarred over, but they’re still there.

Nick’s disability is different. The first of my two gorgeous children, he was born with cerebral palsy in 1988. In my book, The Four Walls of My Freedom, I wrote about receiving Nick’s diagnosis this way:

The white haired doctor stooped to look closely at Nicholas and asked “Has anyone spoken to you about your son’s development?” “No”, I answered, “He is small because he was a bit premature at 33 weeks. Someone crashed into the back of my car at 26 weeks and they think that’s why he was born early”. Only later I learned that “development” meant cerebral palsy or mental retardation.

Three months later, Nicholas was admitted to hospital so that tests could be performed. The doctor asked me if I would like to hear the results. I nodded. She closed the ward playroom door for privacy. We were alone. She in her lab coat was sitting in a sturdy mother’s wooden rocker. I was squeezed into a plastic child’s chair. Around us lay discarded toys and empty chunky bright tables and chairs, all toddler sized. Tears glistened on the doctor’s cheeks as she told me my baby was severely disabled. “Never be normal” are the words I remember. I also remember “generalized cerebral atrophy”. Pea brain, I wondered? “Oesophageal reflux”, she said, “Nothing to keep food down where it belongs. Common in cerebral palsy. Pain similar to heart attack”. There were blue stripes on her blouse. I looked down and something red caught my eye. Blood was oozing from the edge of my thumbnail where I had bitten it. “Well, I’m in the right place”, I thought.

I stood up and felt a lightness, a sense of relief and purpose. “Now I will be able to feed my child”, I thought. “I will become an expert; I will apply myself to becoming a great mother, and my baby will grow into someone perfectly perfect.” Passing the desk, I noticed the nurses half turned, whispering, their pitying eyes fixed on us. I scooped up Nicholas, deposited him into a pram and paraded up and down the hospital halls, back straight, eyes fixed straight ahead. But I was not alright. I wrote in our baby book: “February 22-25, 1989 Nick admitted to hospital. Cat scan, PH probe and digestive barium xrays All abnormal – we trying (sic) to absorb this terrible news.”

I remember hearing a radio news report a long time ago about a terrible road accident in rural England. A young family – parents and three children – had all perished. The grandfather’s public response was “I don’t understand – we brought them up so carefully so nothing like this would ever happen”. I felt like this grandfather – the experience of falling victim to random tragedy and a serious derailment of one’s life plans caused such profound shock and questioning of all I believed was solid and true.

Now Nick is 25 and living a rich, busy and engaged life with full-time care in a home away from ours. To me, his disability is as normal for him as being able-bodied is to me. That said, his disability did derail all my life plans. But, you know what? I’m OK with it – I’m happy with the way my life has turned out. Perhaps I wouldn’t be writing those words if Nick was ill or in pain, but he’s not. Just a disability by itself can’t hurt us.

My Mom doesn’t have a disability per se, but she is getting wobbly on her feet, she’s getting very, very tired and she has troubl

e mustering up the energy to do things for herself. When I think of my mother, I think “well, it’s natural… all this getting old and needing help. It’s part of nature.”

Dad’s disability didn’t feel right or natural and neither did Nick’s at certain points of his life. But in my mind, their disabilities are beginning to melt into my Mom’s ‘natural way’ of needing help as she ages into infirmity. Maybe the cooling embers of my youthful fire of ‘unfairness’ are due to my own aging. I’m 59 years old and this morning, I noticed my back is a little sore and my knees quite stiff. I shrug and pour myself a coffee.