“I discovered that people with disabilities have been major players throughout history. If you were to take away their contributions, you wouldn’t recognize the world.”

I can’t remember the last time I read a book so quickly. I’ve heard of people “devouring” books and always wondered about that terminology but now I know how that feels. I meant to read a few pages – it’s a snowday here, the second dump in a couple of weeks and while the first was much worse, everyone is still tender from black ice and fender-benders and the college is closed, my students are set free to, hopefully, have snowball fights (more typically they try to catch up on their APA despite my intention to be a bad influence like Auntie Mame) and suddenly there are hours that have nothing attached to them…

I can’t remember the last time I read a book so quickly. I’ve heard of people “devouring” books and always wondered about that terminology but now I know how that feels. I meant to read a few pages – it’s a snowday here, the second dump in a couple of weeks and while the first was much worse, everyone is still tender from black ice and fender-benders and the college is closed, my students are set free to, hopefully, have snowball fights (more typically they try to catch up on their APA despite my intention to be a bad influence like Auntie Mame) and suddenly there are hours that have nothing attached to them…

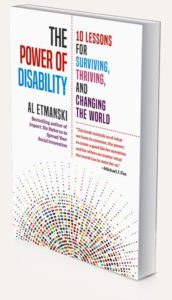

The book, which came out just today, pours into the space that has been waiting for it for months, maybe years. I mean this literally, as Al told me about this book during lunch one day, perhaps two years ago, and Liz and I have talked about it, and I had a vote in the title when that was happening – though I can’t remember if my tribe won. But I also mean it in the bigger sense – I was struck by wondering what this book might have meant to me at the beginning of my career when so many of the ideas in it were things I intuited when I was with people with disabilities, but which the systems I was involved in would not let me hear.

So it’s a bit dangerous, eh? What if, after waiting so long for it, it disappoints? As I am so often disappointed by things to do with the folks I care about, who happen to have had a label at some point.

Instead, it exalts. Like visiting an ancient church or temple created over generations the book is evidence of something numinous, a kind of path that did not exist until it was made manifest. A kind of unveiling of a labyrinth and a map that shows where we are, where we have been, and how we might make our way into the future.

I mean, it’s all my friends, to make a statement of disclosure. People I adore – Jack Pearpoint, Barb Goode, Lynda Kahn, the late Judith Snow, David Roche – to name a few. Vickie Cammack, who is one of my heroes, is here and her energy is throughout. Al himself has been a great mentor and the source of some of the most important and transformational conversations of my life and career – in his former incarnation as the E.D. of B.C.’s largest advocacy network, he gave us advice that saved the agency I worked at for thirty years and allowed us to go on to do things that I am very proud of, and he gave impetus to the creation of the family driven organization that I volunteer at and believe in, and he and Vickie were instrumental pioneers in the creation of PLAN, which I think is one of Canada’s great contributions to civilization and more recently when I was complaining about some aspect of government, he changed my thinking yet again with the statement, “But there is no ‘them’; there is only us.” And… it’s Liz, who is one of my best friends and a great partner in our facilitation work. In fact, is the only person I can draw with when I do graphic recording. Someone once told her it was nice to watch us draw together, and she said, “Yes, I’m the only one he can draw with.” They asked her why that was, and she said, “Oh, it’s because I know what he’s going to do before he does it.” Pretty much, though it is not an equal gift – I often have no idea what she is going to do and every time we work together I learn something that changes me and I become more who I want to be and so does the world become more what I hope it can be. Liz, in stories and quotes and reflections is throughout this book. To attach this to my own field of studies in leadership, Liz leads, in this book.

I was pretty much sold when he began by writing about an idea that I have been talking about for a while:

As you are about to read, people with disabilities have been instrumental in the growth of freedom and the birth of democracy. They have produced heavenly music and exquisite works of art. They have delighted children and the young at heart with some of the most popular stories ever written. They have made us laugh, touched our souls, and taught us how to love. They have unveiled the secrets of the universe. And they have been on the front lines fighting for justice. They are still doing all those things and more.

Exactly. He goes on to make interesting points about folks with disabilities as a “market” that would be good for us to consider – how many of them there are, and how many of them have networks around them that are also believers in what they bring to us and in their capacity to change the world.

He makes a few claims about his intended readership, but I think this one will give the prospective reader the best sense of where he is going:

The Power of Disability is designed to be a source of everyday wisdom for the everyday reader. Each of the ten lessons in the book has a short explanation of why I chose it, followed by multiple real-life stories, many of them about people you know. These are sprinkled with quotations and “Did You Know . . .” facts. Each profile is a bite-sized chunk of a well-rounded and fascinating life.

Yes, sort of. I mean, when I re-read this part I could see that he was describing the shape of the book, but I’m also still feeling my own descriptions – it’s a labyrinth, it’s a map, it’s a church, it’s a path, it’s a temple, it’s an exalting song – are also true. And I was surprised that there were “ten lessons” – it felt like far more.

For example, this is, not least, the story of a father and his child. I’ve heard parts of this story from Al and parts from Liz but I really love how this book holds that story in a way all of us who have children that differ from what we were expecting can relate to and, I suspect, will process in our own ways:

Since then, I’ve asked myself why I thought my beautiful and precious baby daughter needed to be fixed. Part of the answer is personal. I was a driven idealist who pursued perfection at all costs in my personal and work lives. I strived to be strong in everything I did. I was impatient if others didn’t measure up. To be blunt, I was indifferent to people with disabilities, although I didn’t mind helping out those I met. I couldn’t understand why some of my university classmates were so keen to pursue a career in the disability field. I wince when I think of the hard-hearted person I was back then.

I have also come to appreciate that I was under the influence of inaccurate stereotypes about people with disabilities. You are probably familiar with some of them: People with disabilities as childish innocents and eternal children, or endowed with superpowers sent to save and amaze us. People with disabilities as Frankenstein-like menaces, unlovable and dangerous, best kept separate from society for their safety and ours. I’m guessing you can think of movies and pictures that reinforce these stereotypes. The doctor who delivered Liz and who told Liz’s mom and me that he had bad news for us was under the same influence. So were the nurses and social workers at the hospital who asked us whether we would be bringing her home with us or giving her up to foster care. Imagine asking new parents such a question. Sadly, it still happens.

Beautifully elucidated, this captures a parent’s story that families often share, but usually only to each other. It reminds me of Dale Evan’s book, Angel Unaware, that changed so many people’s minds about disability and also provided the seed funding for all of the community support organizations in the U.S..

As such, it is a gift to the wider world that, as this book suggests, requires such gifts to be complete, and indeed, which we have already benefited from:

… even though the history books have missed most of these achievements or have given credit to someone else. I also discovered a debt unpaid. People with disabilities have given the world far more than the world has given them. They have made their contributions throughout history while contending with mistreatment, neglect, and terrible atrocities. They have had to fight for every ounce of support and opportunity in order to survive, let alone thrive and change the world. That’s at the best of times. At the worst of times, people with disabilities have been sterilized, locked up, and killed. Few people realize that the Nazis practiced their mass killing methods on people with disabilities first.

This made me think of a group that Liz and I were working with up North. People were talking about their feelings in segregated places and when they were not welcomed. Liz was drawing and then, for one of the first times in our work, she simply took the microphone and handed me the markers and started talking about the gas chambers of Auschwitz and the experiments done on people with disabilities as a trial run to the atrocities that would follow. “It’s like that,” she said, “People taken from their families and stripped of everything human and then killed in those places and their families were somewhere else, wondering about them and hoping they were okay. They were on the other side of the barbed wire.” Her audience was spellbound. “Whether we are in a room alone, or behind barbed wire fences, we should never be left out.” The supporters of the people gathered for our workshop told me later that they would never forget this and that it had changed their whole approach in moments. The power of her making such statements, while her dad makes his own statements in his own way, is profound.

I am excited to introduce this book to people – to parents, to students, to other instructors and disability supports leaders, with and without disabilities. The writing is so good, I think it will be very readable to even plain language enthusiasts like Barb Goode (I’ve ordered her a copy so we will see what she says).

I feel called to end this with some images by Liz, one from a recent class we taught together with Dr. Susan Powell, in which we showed people how to draw on their Ipads and talked about leadership. She is so vividly represented in these pages but I missed her pictures!

You can order the book from Al’s site or find it on amazon or request that your local bookstore carry it or that your library have it, because librarians, in our experience, are always on the lookout for good books about inclusion.